From "Ca-bau-kan" to "Pai Kau" and Beyond

Indonesian director Sidei SALEH and actress/producer Irina CHIU were the guests at a symposium hosted by Kyoto University professor YAMAMOTO "Hiro" Hiroyuki at the National Museum of Art during the Osaka Asian Film Festival on Thursday entitled ‘From "Ca-bau-kan" to "Pai Kau" and Beyond’.

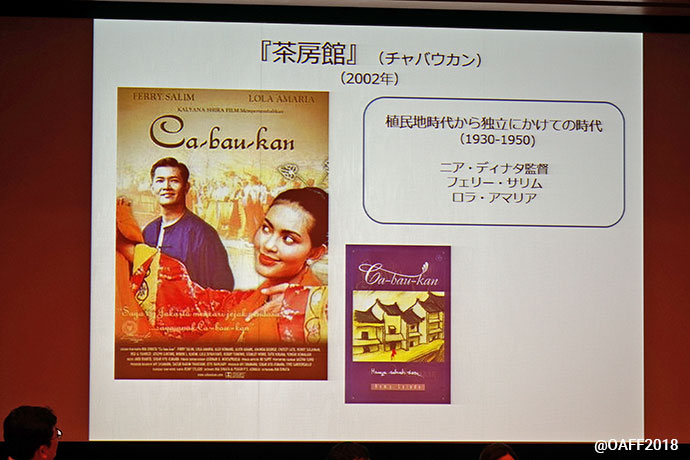

A decade-and-a-half after Nia DINATA’s breakthrough "Ca-bau-kan" (2002), one of the first Indonesian films to revolve around a Chinese community, SALEH’s "Pai Kau" is the latest feature to be set in an Indonesian-Chinese milieu. It had its international premiere in Osaka a month after its domestic theatrical release.

INTRODUCTIONS

SALEH: First, I’d like to thank the festival for inviting me. "Pai Kau" is my first feature after a long period of collaboration as a cinematographer, after which I directed a few short films. I finally made my first feature film with Irina. It was shot in 2016 and was released almost two years after it was completed.

CHIU: We’re excited to be here. I’m really enjoying Osaka as well. "Pai Kau" is the first feature film for myself and for my fellow producer Tekun JI. The goal was to make a new, fresh and entertaining movie in Indonesia. It’s a suspense drama. In Indonesia, there hasn’t been so many suspense dramas produced so far. So we’ve gotten a very positive response from the audience there and we’re really excited to see what you think about it and hear any questions that you have.

Director: Sidei SALEH

Producer/Actress: Irina CHIU

ORIGINS

CHIU: Actually my background was not in film. My background was in banking and the finance industry. Acting [in theatre] was only my hobby. One day, I decided to focus on acting and I quit my job. At that time I was working in Singapore, so I returned to Indonesia and tried to get into the film industry there. After a few acting roles, I realized it wasn’t easy to make it as a newcomer. So I put my destiny into my own hands and made my own film, partnering with another producer. We started to scout for directors that wanted to work with us. We went to many filmmaking workshops and screenings until we watched Sidi’s film Sidi's film "Maryam". It won an award for best short film at the 2014 Venice Film Festival. At that time, we knew that we wanted to work with him. We had coffee together and discussed a lot about filmmaking in Indonesia. Although my co-producer and I were not experienced in filmmaking, apart from making a very short film in our house at the very beginning. From there, things went very quickly. We started developing a story. The idea for "Pai Kau" came from Sidi. We discussed the direction of the story, whether it should be more drama or more suspense. Then Sidi and another scriptwriter developed it. The journey was about two years before we screened "Pai Kau".

SALEH: I’m always nervous when discussing a film like this! Why I worked with Irina, and how we met, has already been outlined. My concern when my producers come to me and talked about films is that Irina and Tekun are Chinese, Indonesian-Chinese. At that time, I didn’t have any interest in using Chinese characters in my stories. Indonesian films with Chinese characters are always focused on minorities with political statements. For me, I don’t feel like digging wounds. It doesn’t mean that I don’t care. It just doesn’t interest me [as a director]. I told Irina that if I wanted her to act in one of my films, then probably I can write a new story for her. And then the discussion about "Pai Kau" started.

WEDDINGS

CHIU: The weddings in Indonesia nowadays are held in a very, I can say, mixed or modern way. Depending on the person’s cultural background and their religion, there will be certain aspects of their culture that will be part of that wedding. So in the story of "Pai Kau", there are elements of Chinese culture. For the few here that have watched the movie, the tea ceremony, for example, is a very Chinese tradition. Since the family is Catholic, the wedding ceremony itself is held in a church. You can see that in real Indonesian life. Nowadays, the weddings are a combination of various [cultural] elements. In "Pai Kau", it’s quite realistic how the wedding is presented.

SALEH: I was working as a wedding documentarian in my younger days, when I was still in high school. Scenes of Catholic marriage are not often portrayed [in local cinema]. In Indonesia, I only see that in Hollywood films. For example, the bride being brought to the groom by her father. In Indonesia, that’s not normal. But nowadays, the young generation copy from the west. In Indonesia, we have some events before the wedding that we call “lamaram”, which translates as “engagement” but it’s more than that. In Indonesia, the engagement is not just about exchanging rings on your knees, it’s also about the two families meeting and approving of each other. That’s why I used the scene from my own experience. I have all the brides and all the fathers walking together. In the past three years, young couples are starting to copy that. But before, in the 1980s and 1990s, at least from my own experience, it was never like that except in the movies. I myself am Muslim, but I have friends who are Catholic and Buddhist. It was quite a long discussion [with my producers] whether to use a Catholic family. I considered using a Buddhist family, but it would be less interesting because the Buddhist ceremony is not that complex. As the writer, I choose to use the Catholic family because at least I could ask friends about the logic of the ceremony. In "Pai Kau", I’m also using the concept that “what is united [by heaven] cannot be separated by humans”. I find these words really interesting. At least for myself, for Muslims, after marriage it is sometimes so easy to divorce. It’s a contradiction to me, something I need to understand as a human. In every religion, there has to be a way to create security. So that’s why I used Chinese Catholics for this story. It really gave me a new perspective as a writer as well as driving the plot.

CHIU: Traditionally, the bride is said to join the family of the man. In reality, it depends on other factors such as the type of relationship, and power and wealth may also play a factor. In the film, Lucy’s father is very wealthy so it’s as if [her fiance] Edy marries into her family. But it’s still the tradition that the woman marries into the man’s family. Now, it’s much more modern. So it’s not like the daughter belongs to the family of the man. It is now seen as much more equal.

CHINESE CONUNDRUMS

SALEH: The script was written in Indonesian. Then we brought in translators for the Chinese. At first, I wanted to film half the film’s dialogue in Chinese, but in practice there are many issues about the availability of [Chinese-speaking] actors in Indonesia. I realized it’s really hard to find them through casting; the reality is not simple. Some of them were found through the casting process but some I scouted by myself. Some are even relatives. Irina’s father is one of my victims! I asked him to be the father of [CHIU’s character] Lucy. So, it’s a fiction on a reality and a reality on a fiction. In the Chinese restaurants, we have four or five characters but only two of them speak Chinese in their daily life. That’s why I decided not to shoot the whole film in Chinese; only half the dialogue. I chose three scenes to shoot fully in Chinese, two of which are 7 minutes long.

CHIU: My father is an academic and researcher in biochemistry and biotechnology. He lectures at an Indonesian university where he specializes in nutrition and health. So he’s very far from the acting world! But he wanted to support us. Actually, I myself do not speak Chinese. “CHIU” is part of my Chinese first name. My surname is Tan. I’m using “CHIU” because it’s a part of my name - meaning “spring” in Chinese - that I like. And Tan is too common in Indonesia! The Chinese language spoken in the film is Mandarin. Standard Mandarin. But it sounds different from that spoken by Chinese in China. It’s closer to the Chinese spoken in Singapore or Malaysia. But we wanted to use standard Mandarin Chinese because more people would understand that than Hokkien or Cantonese in Indonesia.

SALEH: In reality, Indonesian-Chinese don’t speak Chinese in public. They only speak Chinese in private. In Indonesia, the government is promoting one language. When we tried to find actors, it was really hard because even for those that speak Chinese, it’s not in the same dialect. One speaks Mandarin and another one Cantonese. When we decided to use Mandarin, we found actors that could at least speak a Chinese dialect and have a translator on set to correct their pronunciation.

CHIU: The Indonesian-Chinese in their 60s or 70s are mostly able to speak Chinese. And the very young children who are maybe 4-, 5-, 6-, 7-years-old can speak Mandarin because it is now taught again in schools, and may even be a mandatory subject. The Chinese schools were closed towards the end of the 1950s. After that, until the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, people didn’t learn Mandarin in schools so they were unable to speak it. That’s my generation. Among my friends, 80% or 90% of them are not able to speak Chinese.

SALEH: We have one poster that we use both inside and outside Indonesia. The title is written as “Pai Kau”. Why? I’m also confused. When I tried to understand the game of “pai kau”, of course I asked Google first, and then I asked various people. I’d ask friends when I visited them in Kuala Lumpur and everywhere else that I had the chance. And there were many different explanations of the game. I realized that the Chinese language has many dialects. I always ask the translator on set to please give me a signal if the actor’s accent is wrong. Finally I decided on this title because the spelling is easier for Indonesian people to pronounce and remember. In Indonesia, they often spell my name wrong with a “k” at the end!

CHINESE AS A MINORITY IN INDONESIA

CHIU: I think that’s an interesting question. When people talk about minorities, they are usually discussed as at a disadvantage. While Chinese-Indonesians are a minority in terms of their number, they are not a minority in terms of being taken advantage of in society. So while maybe historically there were many events that led to Chinese being at times suppressed, at other times the situation made them more active in the economy and in trade. If we look at the picture nowadays, it is correct to say that the Chinese are an important force in trade and the economy in Indonesia. In films, we tend to only highlight the Chinese in upper parts of society, whose lives seem to be so interesting. But the middle-class Chinese face the same struggles as everyone else in society. There are Chinese-Indonesians who hold the power, but most of the Chinese in the nation adopted one of the five major religions: Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Hinduism and Buddhism. I’m sure there are certain groups still practicing Taoism. From my personal experience, I don’t think many Chinese-Indonesians are that connected to Chinese philosophy such as Taoism or Confucianism. That’s from my own experience.

TEN YEARS LATER

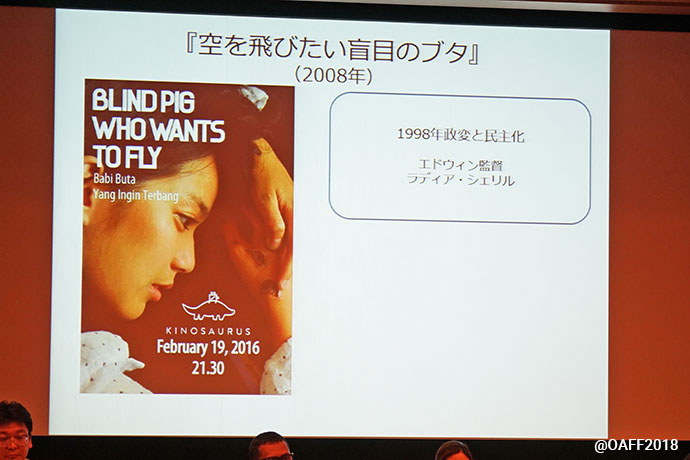

SALEH: Ten years ago, I was in Osaka, as the producer of [Edwin’s] "Blind Pig Who Wants to Fly", an independent film. In 2018, I’m making films in the same way. When I arrived here in Osaka, I realized that I’m still independent and struggling in many ways. The difference is just the particular team and the particular content of the film. "Blind Pig Who Wants to Fly" was trying to criticize the situation [in Indonesia] at the time. Now I’m still criticizing something but it’s not about social issues but about the economy. The population of Indonesia is now over 270 million people. And it’s still growing because we still believe in love! We now have an issue about “place”, about finding the venue in which to show our films. Film production is in a dilemma. As well as struggling to find space in cinemas, we are now facing the digital platform. In my neighborhood they are a lot of salesmen selling motorbikes or cars easily, promoting them on just a slip of paper. But in filmmaking, the whole marketing and distribution process is much more complicated. We are thankful to a lot of film festivals. At least they can be the place to show our films. In Indonesia right now there are only about 2000 cinemas that serves the whole population. It’s a small number of cinemas to handle all the regions. If the industry is to grow, there’s great potential, providing there are more cinemas. And I think it’s going to really happen. And piracy is not really a problem anymore. All the piracy stores are closing. Because the internet has everything. And a lot of digital platforms are now making the process of watching films easy. So websites of piracy films have started to close. The government with the push of the producers is helping to shut them down. Of course it’s not 0%, but I think the situation continues to get better.

CO-PRODUCTIONS

SALEH: I worked with Japan’s SUGINO Kiki on her film "Taksu" in 2014 as her cinematographer. We tried the possibility of having co-productions but it’s tough. Sometimes the issue is the story. That’s the first issue. Then the story is going to lead you onto the issue of casting. And then, the last part is the hardest, dealing with the taxes! All filmmakers want to make many kinds of movies; we have a lot of creative stories to tell. But sometimes that demands doing a co-production between two or three countries. But the chance is very rare. It tends to be films aimed at Cannes, Venice or Berlin. But a lot stories don’t suit that kind of festival. It might be an interesting story but it’s not suited for one of the big three festivals. Sometimes it’s about the trade deals between two countries. When we work together, it’s like smuggling people across borders. The money is not always the biggest issue. It’s not the most important thing for generating ideas. If we have a common issue, and the same passions, then we will find a way to finance it.

ORIGINAL STORIES VS. ADAPTATIONS

CHIU: In Indonesia, films based on very popular novels usually have higher success as they already have a big follower base. Apart from that, a popular model in Indonesia is when a film is a huge hit and years later a sequel has almost the same level of success. Concerning original stories, I do think that they have a harder time to be introduced to the public. It usually helps to have a well-known actor or actress in the movie to attract an audience. People don’t watch a film just because a director or screenwriter is famous. They go to see films based on the faces of the actors.

SALEH: Film should be universal. Many films that succeed in Indonesia are very simple. With "Pai Kau", we are trying to put together two ways of making films: it’s a bit layered [like an arthouse film] but it’s still using a commercial [cinematic] language. It’s a laboratory film, experimenting with the way of filmmaking. This is my way to learn.

CHIU: For me, it was important to dare to do something bold. To have the courage to do something fresh that has not been done before. We didn’t want to repeat the same kind of stories or combine the same elements as before. We also wanted to add to the diversity of the Indonesian film landscape. For me, and my Indonesian-Chinese co-producer, there are not so many Indonesian-Chinese in the film industry, they are perhaps more behind the camera but not in front of the camera. And there are not so many Indonesian-Chinese actors yet. So it could open more possibilities for them to become more active.

FINAL WISDOM

SALEH: Love your family and don’t mess with women!

- Transcribed by Stephen Cremin